Conjoint analysis design

Conjoint analysis and trade-off studies are amongst the most powerful forms of market research. The aim is to quantify the underlying values (utilities or part-worths) that drive customers' decisions, and then to build models of demand and market forecasts, in order to optimise product or service features.

Conjoint analysis and trade-off studies are amongst the most powerful forms of market research. The aim is to quantify the underlying values (utilities or part-worths) that drive customers' decisions, and then to build models of demand and market forecasts, in order to optimise product or service features.

The quality of the outputs depends on creating a good quality, realistic, design. For conjoint analysis, in particular this means choosing the right flavour or type of conjoint to use and ensuring that the design of the attributes and levels, the way the profiles are shown and the number of choice tasks matches the real world, while also stress-testing business plans and strategies.

Type or flavour of conjoint

Conjoint design starts with the choice of the flavour or type of conjoint analysis that is to be used - choice-based, adaptive or some other hybrid version. Most common is Choice-based Conjoint (CBC) and often this is given as a default options. However, different conjoint flavours do exist, and do have different strengths and weaknesses, particularly as the number of attributes grows. Alternative approaches (eg MaxDiff) may be more applicable depending on the objectives of the research.

All conjoint designs can be carried out on computers or phones. Some older techniques can be carried out on paper but this is mainly for students. Phone-based conjoint is difficult unless you use a web-assisted telephone interviewing approach as describing products purely verbally is difficult. More advanced conjoint flavours like menu-based conjoint, partial profiles, ACBC and others allow large complex designs, others are more robust in the face of issues like pricing. Note that the form of conjoint design also affects the analysis method needed.

Attributes and levels

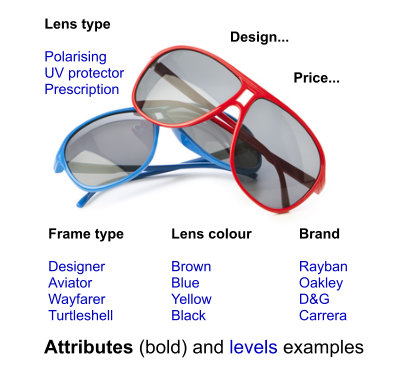

The second key element of the conjoint design are the attributes and levels that make up the product or service.

Attributes and levels describe the product features and options that specify the different products available for purchase (see below). CBC typically deals with 5-8 attributes.

Larger numbers of attributes and levels need different conjoint approaches than designs for simpler products with small numbers of attributes or levels. Software and service design commonly have many more attributes

Exploring attributes and levels

You can explore Conjoint designs and flavours with the Cxoice Conjoint Explorer to find out how these parts work together.

Conjoint analysis is a sample-based research method, so the final element is designing the sample itself based on the contact methods available. Can the interview be carried out face-to-face, or over the internet, or by post and phone, and how long will the questionnaire be?

What are attributes and levels?

Attributes and levels form the fundamental basis of conjoint analysis. The idea is that a product or service can be broken down into its constituent parts - so for instance a mobile phone has a size, weight, battery life, size of address book, type of ring. Each of these elements making up a generic mobile phone is known as an attribute.

Attributes and levels form the fundamental basis of conjoint analysis. The idea is that a product or service can be broken down into its constituent parts - so for instance a mobile phone has a size, weight, battery life, size of address book, type of ring. Each of these elements making up a generic mobile phone is known as an attribute.

When we compare between mobile phones each will have a different specification on each of these attributes. You might have choices in terms of battery life between 72, 108, 120 hours of battery life. Each of these options is known as a level of the battery life attribute.

So to give another example, a car might have an attribute 'colour' which is made up of the 'levels' red, blue, green, white.

Thinking of attributes and levels strategically

This breaking down of products and services into attributes and levels is an extremely powerful tool for examining what a business offers and what it should be offering. For new product development, combining this product breakdown with an understanding of what the customer values most means that the business can focus its efforts on those areas of most importance to customers.

How to choose which attributes and levels to include

Basic conjoint analysis is limited in the number of attributes and levels it can include (advanced techniques offer more options). Because of this it is necessary to identify and prioritise the attributes to be tested. While these seems simple for small designs, in practise there are trade-offs, and each description needs to be framed in terms of something a customer would buy.

To identify attributes and levels, our standard approach is to run workshops that explore a typical customer journey and investigate all the potential uses and touch points for a product from finding initial information, to opening the box, using the product and down to factors like cleaning, security and problems. It's common to find more than 200 attributes which then need to be whittled down to the key attributes and levels that need to be measured.

Attributes and levels as measures of performance

In addition, each level can also be thought of as a performance target. If the customer, on the attribute 'delivery', wants the level "next day delivery" and we're perceived to be offering "48hr delivery" then there is a gap to make up. What is more with conjoint analysis, it is possible to calculate what the value of making up that gap is to the business. Compare this to the cost of doing it and the business can decide whether it is worth it.

Note that this is far more useful than simply knowing that we score 6.9 out of 10 on delivery. This has no meaning. It doesn't say where the customer thinks we are and it doesn't tell us what we need to do to get higher, or whether it is worth trying to improve this score, or what it will cost. For a lot of strategic work attributes and levels are far more powerful tools than scales and scores.

Rules around attributes and levels in conjoint analysis

In conjoint analysis, attributes and levels have to follow certain rules to ensure the conjoint is valid but there are also best-practice design criteria to make them particularly useful.

- Independent (no overlaps)

- Standalone

- Sufficiently comprehensive

- Affect purchase choice

Firstly, each attribute has to be independent, that is it should not overlap with other attributes. So colour and fuel economy are clearly not related, so they could appear together. However, some things like "car shape" and "number of passengers" aren't independent - a 7 seater coupe isn't realistic.There are also more subtle effects - certain attributes have halo-effect on others around them. For instance, if one level were "gold-plated handle", many people would infer that the rest of the product was also of better quality when there is no other information to support this. The main difficulty this causes is that price and brand need to be treated extremely carefully in conjoint studies to produce valid results.

Each level also needs to be capable of being read and understood on its own. Although attributes are used to help break a product down and in analysis, when presented to respondents all the respondent sees are the levels.

Making conjoint analysis realistic...

Independent and readable levels are important from an analysis point of view, but for the conjoint to be useful it also needs to be realistic - to reflect real customer decision-making. For instance, to ensure that the range of attributes cover all the areas that are important to the customer, and that the range of levels cover all possibilities from worst-case to blue-sky.

Mixing product and service elements

For many products, particularly in business markets, service can be more important than the actual product. By using both product and service attributes in the same conjoint it is possible to see how customers trade-off service against features. However, care has to be taken to balance the attributes to prevent biasing the outcome one way or another.

Making descriptions actionable

It is also vital that the levels used describe real and where possible measurable and actionable performance. You could run a conjoint with levels "very good fuel economy" "good fuel economy" "not so good fuel economy". But, as with the scales above, these don't mean anything. If you come out with "good fuel economy" and the customer wants "very good fuel economy" what do you do?

One good test is if you showed it to the shop-floor (or the call centre) would they know how to deliver it. A second test is whether it is a statement you could use on a packet or in a brochure.

The look and feel of conjoint - dressing the survey

Realism also plays out in the look and feel of the conjoint on screen. The ultimate aim is to try to replicate a purchase choice that a customer might make in real life. Words, images and layout all help to place the consumer in a realistic purchase situation.

Our Cxoice Survey Technologies were originally developed because we needed tools to make conjoint and trade-off tasks like configurators more realistic and more visually appealing than other conjoint software. With care conjoint analysis mimics real consumer decisions, and it is only through this realism that results will model real behaviour in analysis and reporting.

Creating the design

Producing a good conjoint design means working with product and service managers to identify what has to be measured, and how it is best communicated. Unlike open surveys which can be vague with terms like 'good' or 'better', conjoint designs need to look like real products. Creating the design often helps focus on what the key deliverables and options for a product or product range can be, and getting that strategic thinking together can make a conjoint project worthwhile, even before the project heads to fieldwork.

Discover more...

- Conjoint history

- Conjoint types or flavours

- Interactive Conjoint Explorer to test designs and flavours

For help and advice on carrying out conjoint analysis or other market research or market forecasting, contact us on info@dobney.com