Strategy from market research

Strategic market research identitifies what value means to customers, what they need, willingness to pay and how to define and reach your target audience. It then identifies strategies and tactical wins to deliver clear, business-enhancing results focused on maximizing customer success.

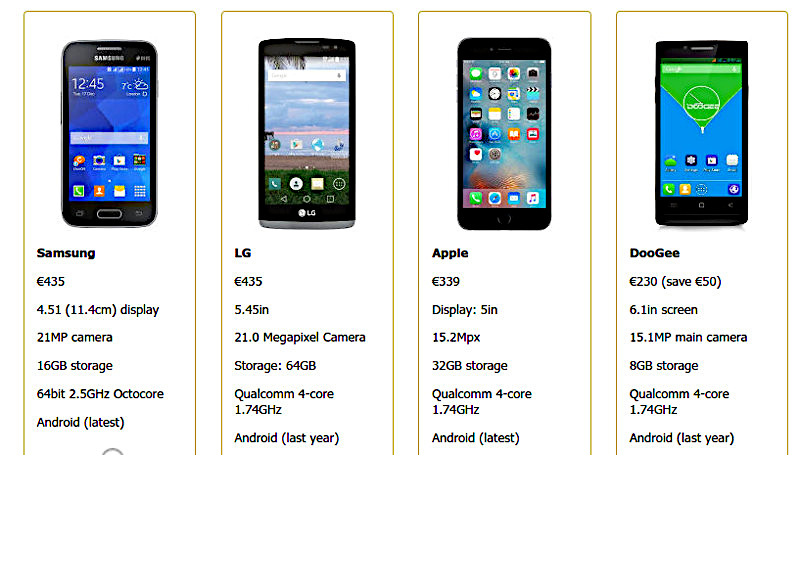

Conjoint analysis - what really customers value

Customers know what they want when they see it but can't always say what they need - the say-do-gap. Conjoint analysis is used to ensure products, features and services are validated by real choices and preferences.

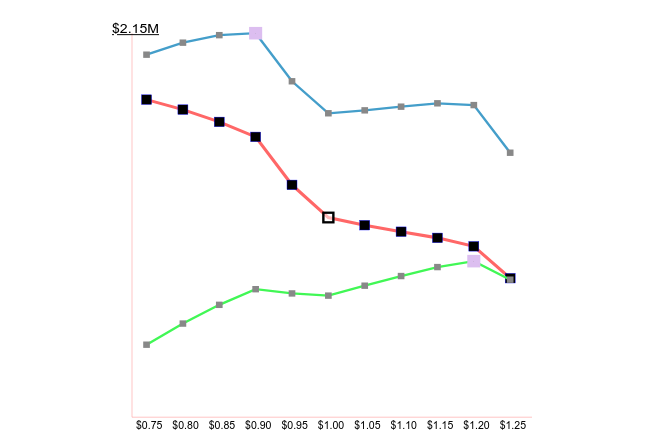

Master pricing strategies and willingness-to-pay

To understand what customers are willing to pay, you need to understand what really drives value. Our pricing research evaluates the impact of pricing and how prices affect customer demand to build pricing models and forecasts around core willingness to pay, feature-value and price optimization points.

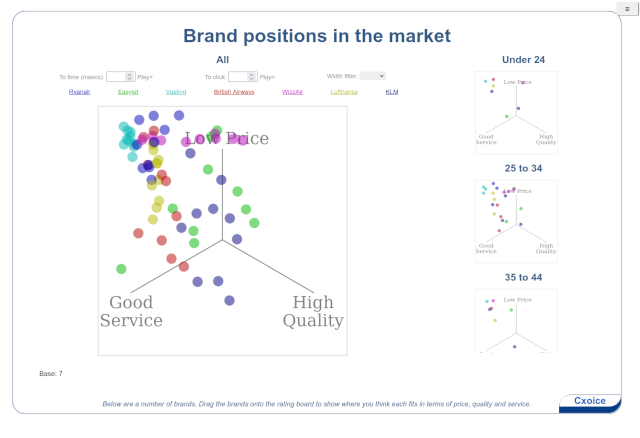

Research that goes in-depth

Market research is key to stay ahead of competitors. Market size and segmentation define your market. Brand and advertising tracking checks that your marketing is working and delivering value. Satisfaction measurement checks that your products and services are continuing to meet customer needs.

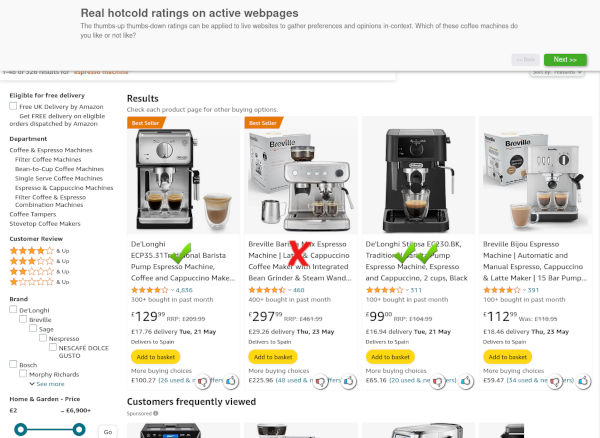

On-going feedback can include video or speech-based AI, and web-overlay surveys to keep up-to-date with customer needs.

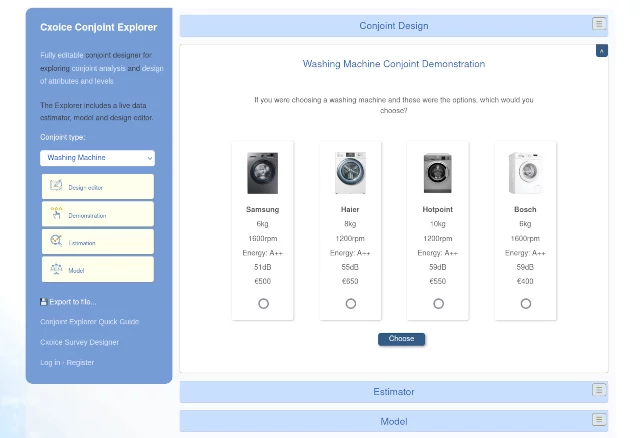

Cxoice - the end-to-end research platform

Cxoice Insight Systems platform is our bespoke survey platform from years of building better surveys.

Cxoice delivers research that is more engaging, more visual, more realistic and more relevant for your customers. Highlights include web-overlay surveys, video capture, AI and automated analysis. Cxoice is the real-world insight system you need, with AI where you need it.

Research for decisions

Research is not just about asking questions, it's about asking the right questions based on the needs of your team, and the needs of customers, and understanding your sector and features.

Listening, learning and advising are one of our great strengths. We're not just selling surveys and fieldwork.

Our approach

Explore

Work with your team. Understand your business needs. Map out the market structures. Generate hypotheses. Scope the options.

Experiment

Investigate and test customer preferences and opinions with tools like conjoint analysis or web-overlay surveys

Discover

Build market models and sales and revenue forecasts to identify sweet-spots and the most impactful messaging and communications.

Why work with us...

We have more than 25 years experience of working with blue-chip companies and start-ups to ESOMAR industry standards. We work across sectors from toothbrushes to technology giants, from newspapers to financial products.

Our experts are used to challenging business and marketing problems often involving leading-edge technical products and services where research is only part of the puzzle. Having our own survey platform we can solve even the most complex research challenges and marketing experiments.

Contact us at enquiries@dobney.com, or call +44(0)1633 226 950, or use our help and advice form.